John Jackson – Maker of Billinge Chairs

This definitive study on the subject of Billinge Chairs was submitted to Loughborough University in 1979 by Neale J Banks, as part of his degree course.

We are indebted to Colin Redwood for uncovering this research.

In the course of my researches in the area of South West Lancashire and what is now Merseyside, I very quickly became aware that it is general and common knowledge that there is a type of chair which is referred to as a ‘Billinge’ chair. I found several people, all of whom were either old or middle aged, who had owned or still were in possession of these chairs. Chairs, which have survived in their native area, have done so because of the regard in which they have been treated. Far from being used as garden chairs, or simply for rough household use, such as for standing on to reach up into cupboards, all the chairs which I have seen in these people’s homes have been in beautiful condition. They have acquired the mellow, warm glow of genuinely old pieces of furniture, without having been subjected to the rigors of hard use. In modern days this is of course quite understandable; these chairs have now acquired a considerable value as antiques. But this does not begin to explain why they were treated so lovingly whilst they were still simply ordinary, everyday chairs. My answer is simply that they were not ordinary or everyday. In the relatively poor social climate of Billinge in the early nineteenth century, Billinge chairs such as have survived were seen as something of a status symbol. One of the old ladies whom I interviewed, Mrs. Ethel Heyes of Main Street, Billinge, put this point beyond doubt. In response to my query on this question, she said

“Ee, if you ‘ed Billings cheers (hesitating) well, you woe IT!”

Mr. Edward Birchall of Ormskirk Road, Rainford, who lived all his younger life in Billinge, provided further reinforcement to this point. He told me of how his mother had reacted to the mistreatment of her Billinge chairs. Mr. Birchall’s elder brother had brought home a girlfriend, a farm worker by the name of Ada for his mother’s approval. An irate Mrs. Birchall forcefully evicted Ada from the parlour, for sitting with her clogs on the front rail of Mrs. Birchall’s own rocking chair. The lives of these two prospective lovers had been violently shaken by the regard for Billinge chairs.

My search for the maker of Billinge chairs were therefore a matter of some personal interest. I think it fitting that this man should have some permanent record made of his activities, in as much depth as I could uncover.

In his article ‘The origins of the English country chair, published In the ‘Woodworker’ magazine, October 1978, Bill Cotton says:

“There is strong hearsay evidence that these chairs were made in the village of Billinge in Lancashire, but the author can find no record of a chair maker having lived there”.

Indeed my own researches using trade directories of the period have shown no reference to a chair maker living in Billinge at any time. My method of approach therefore was on a personal basis. Rather than making a search for formal records, I opted to conduct some interviews with locals to try to unearth some first hand memories. My first call was to the information desk at the local council office at Billinge, where I was very kindly and efficiently given the names of local old people who may be able to help me. My interviews with several old people, which were both helpful and enjoyable, led to an unexpected stroke of luck in my managing to contact a living descendant of ‘the craftsman’, as he is referred to locally.

Mr. Dick Fairhurst, who still lives in Billinge, is eighty-four years old, and is the great grandson of ‘the craftsman’. His depth of recall and the detail of his memory Is remarkable considering that this old man is remembering his childhood impressions. Not only does he still own three of the chairs, which were undoubtedly made by the man in question, but also he owns the very last chair, which he ever made upon his retirement, and even one of the tools that he used.

In this instance therefore I have achieved by primary objective in being able to link a particular craftsman with authenticated examples of his work. I have found however that the ‘Billinge’ chair, which Bill Cotton was referring to in his article, bears no resemblance to the authenticated Billinge chairs that my research has uncovered. The example, which Mr. Cotton illustrates, is a low-backed chair with two rows of five turned, vertical spindles. The Billinge chairs, which are owned by Mr. Dick Fairhurst however, are invariably a high, ladder-backed variety of chair. I am assured that there was only ever one chair maker in Billinge and I am also assured that he never made spindle backed chairs. I think that I can say therefore that the spindle backed ‘Billinge’ chair was almost certainly not made in Billinge at all. On the other hand, I can say with absolute certainty that the chairs, which I have illustrated, are, beyond any remote doubt, Billinge chairs.

Before analysing the features of these chairs however I feel that now is the time to reveal the identity of ‘the craftsman’.

John Jackson was born, raised and worked for his entire working life in Billinge. There is only a little information available about him as a person, but there is considerably more about his activities as a craftsman.

Jackson was brought up as a Catholic, a member of St. Mary’s R.C. Church in Billinge. Billinge was not an affluent community; the vast majority of the working population was made up of coal miners and nail makers. Both these trades entailed working underground, because as nail making was such a noisy activity, social pressure forced it to be confined to the cellars of houses. The 1861 census records several one-man trades, e.g. smithy, wheelwright, cooper, clog maker and a great excess of publicans but here again no reference is made to a chair maker. As a self-employed man, who actually worked above ground, Jackson would have been one of the elite of the village’s working class.

This would presumably have put him on a favourable social footing within the community.

Jackson’s workshop was adjoined to his house at the southern end of the village as it was then. It was sited on a bend in the main road next door to a public house rejoicing in the name of the ‘Labour in Vain’. The building was of solid, stone construction, and the workshop itself was in the form of a long gallery, which Mr. Fairhurst estimated to be about 30 ft. x 12 ft. It had a flagstone floor and a row of windows all along one long wall, probably the southern wall, which faced out onto the main road, so that they would admit as much light as possible. Up in the roof, the ‘A’ frames of the wooden rafters were exposed. It was here that Jackson stored his timber, resting between the horizontal members of the roof structure. Attached to this workshop was the village smithy, where Jackson bent his back slats over steam. Memories are a little more vague here; Mr. Fairhurst is not sure whether the smithy was housed in the same building or whether in a separate building next door.

The timber used was locally felled, coming from a wood about one mile to the east of the village at Blackleyhurst. Jackson may have felled his own timber, but he certainly did transport it himself, by means of a horse and cart, which he kept for this purpose. The wood was almost exclusively ash; Blackleyhurst was an ash plantation of considerable size, which was being cleared to provide agricultural land. There are no suitable sources of rushes anywhere in the locality; therefore Jackson used imported rushes. These almost certainly came from the Low Countries, probably Holland, and not, as has been stated in R. D. Lewis’s book, Germany.

One of Jackson’s tools is still surviving and I have been able to examine it closely at the home of Mr. Fairhurst. It is his wooden brace and bit, or as it is known ‘the old ogre’. The word ‘ogre’ is almost certainly a derivation of auger. With this ancient tool Jackson bored the holes for the spindles in all of his chairs. The body of the ogre is made of beech, with iron fittings. The cutting tool is a plain spoon bit; gouge shaped with parallel sides, and is mounted in a square, tapered shaft. Presumably therefore Jackson had bits of different sizes, which could be changed by tapping out the protruding end of the square shaft. The pivot for the curved pressure pad is a turned spigot from the main body. The bearing mechanism is simply wood to wood; the center pivot screw could be tightened down to take up wear. A steel plate is screwed to the rest to take the pivot screw and originally a leather pad would have covered this, which has been lost. The ogre is well worn and is polished with the perspiration and grime of many years of employment.

Jackson’s lathe has been destroyed at some time in the last five years, being broken up for firewood whilst in the possession of another of his great grandsons. Dick Fairhurst remembers ‘two big pieces’, presumably the head and tail stocks. The lathe had an unusual power source, two men were employed to treadle whilst Jackson did his turning.

I have mentioned that Jackson did his steam bending in the smithy next door. The back slats were steamed over an open tank of boiling water whilst supported between rods laid across the edges of the tank. Beneath the tank was a fire, which was fed by workshop waste. My sketch is simply an illustration of a principle, it is not correct in detail, but it has been verified by Mr. Fairhurst. The slats were then placed in a hollow former and weighted in the center as they dried.

No records in the form of bills, receipts, or invoices have survived; Jackson kept no formal accounts. Trade was done in cash only and always in his workshop. Jackson did not have to transport his wares to the local market his customers came to him, which must imply that he was well known locally. His chairs were made in sets of six mostly, and I have been told that he charged £2.00 for a set of six chairs around 1860. Individual chairs, such as rockers could be made to order. No records exist of his designing activities, there are no surviving working drawings for example. The roots of his design are obscure, and I would consider it probable that he simply adapted forms that he had seen, in true vernacular fashion.

Jackson made his last chair in 1870, which is still in the possession of Mr. Dick Fairhurst as I have mentioned. This chair was made from remnants of his stock in hand upon his retirement. Jackson’s last chair is the child’s rocker shown in my photographs, which was given to his grandson, Mr. Thomas Fairhurst. It has reputedly ‘rocked everybody in Billinge over sixty’, in the words of Dick Fairhurst, to whom the chair descended from his father, Thomas Fairhurst. Apparently the children of Billinge used to fight to rock in it.

Jackson gave up his trade because he was beginning to get old and wanted to retire. I am assured that he was not forced out of business by the speed of more modern production methods. His reputation as ‘Jackson of Billinge’ was enough to ensure a continuing demand for his work. After having lived in Billinge all his life he moved to nearby Haydock, where he died with relatives.

Jackson’s grandson, Thomas Fairhurst, re-rushed Billinge chairs in his spare time as a supplementary income to his full time job as a coal miner. Dick Fairhurst remembers carrying armfuls of wet rushes in to his father, from a little stream, which ran next to his shed on Gorsey Brow. The rushes were soaked in the stream to make them supple and then they were put into the chair frames whilst still wet, so that they pulled tight when they dried. He rushed chairs for ls.6d. each, from around 1890 to 1920. Due to this activity being only a spare time job, Fairhurst often built up a large backlog; he reputedly once had over a hundred in his shed waiting to be rushed.

Dick Fairhurst also re-rushed Billinge chairs in his spare time. He also was a coal miner and only rushed chairs during the great depression and during periods of short time working at the mine. At this time, around the 1920s and 1930s, there were still people alive who were old enough to remember Jackson as a person. When they brought their chairs to be rushed Mr. Fairhurst would be able to find out more about him to supplement his childhood memories. Like all old people they liked to talk about old times. Re-rushing was not economic, says Mr. Fairhurst; he could not charge enough to make it worth his while as a living, it was simply helped when times were hard. He could rush two chairs in three days, but says that Jackson could rush two per day, though he does not know how he managed it. The plain Billinge chair in my photograph was made by Jackson, and re-rushed by Dick Fairhurst in the 1930s.

The chair, which I have labeled as a ‘typical’ Billinge chair, is most likely one of Jackson’s earlier versions of the genre. The chair was re-rushed by Dick Fairhurst in the l930s and it was he who omitted the covering strips from the seat edges. It has an almost dead straight back; there is just a slight backward bend in the main back members at the level of the seat. The first impression, which this chair gives, is that it was a turner’s chair, the only parts not turned are the horizontal members of the back. The rear legs are octagonal below the level of the seat and turned above the seat. Very typical indeed of Lancashire chairs are the front legs with pad feet and the front rail with its characteristic double swelling in the center. The Inside edges of the front legs are planed flat to receive the spindles.

The turning was certainly done whilst the ash was ‘green’ or unseasoned. All the turned members are markedly oval due to the drying process having taken place after turning. Bill Cotton, in his article ‘Country Chairs’, suggests that this oval-making process was consciously used by chair makers as a means of ensuring that joints tighten up if they are assembled before the timber seasons. The timber seems not to have been cleft for the legs however. Instead of the characteristic quarter circle of end grain on cleft timber the end grain on the legs of this chair is almost straight. This suggests that the timber was originally obtained from logs of a considerable diameter.

I have decided that this was one of Jackson’s earlier chairs by taking account of several features. The chair, which Mr. Joe Green is displaying, is, I am almost certain, a later Jackson chair and the two can be compared. The earlier chair shows a marked splaying outwards at the top of the back whilst his later chairs were more parallel. More obvious is the shaping on the slats, which becomes much more refined, in my opinion, on his later chairs. Similarly the raised top rail on the later chairs is, I think, a later development from the flat rail on the earlier chair. I will discuss this more presently.

The lady’s rocker, which is owned by Mr. Fairhurst, is a particularly beautiful chair. In many ways it is similar to the simple chairs, but with added refinements.

I had heard from Mr. Edward Birchall that Jackson had made two types of rocker, a lady’s rocker and a gentleman’s rocker. He had told me that the main difference was that the arms on a gentleman’s rocker were higher from the seat than those on the ladies’, but he could not tell me the reason for this. Mr. Fairhurst told me however that the gentleman’s rocker had arms about ten inches from the seat, so that the man could relax and rest the whole length of his forearms. The ladies’ rocker however had very low arms so that the lady could rest her elbows whilst she was knitting or darning - evidently women’s liberation was not established in Billinge in the mid-nineteenth century.

This particular chair is remarkable in that it is not stained; it is one of the very few Lancashire chairs that were not stained a uniform brown. The side view shows the very slight bend in the back, and the octagonal portion below the seat level. It also shows that the pads were still turned on the front legs even though they were to be mounted on rockers. The grain pattern on the rockers shows that they were steam-bent.

Two features in particular make this chair especially attractive in my opinion. The pronounced double kink in the arms is particularly bold and alive. Also, the dominating, crested top rail is a highly developed blend between the leg and the rail. An identical crest appears on a carver that was illustrated by Bill Cotton in his article and this could well be a hallmark of Jackson’s finer work on rockers and carvers.

I am particularly fortunate to have been able to find the last chair that Jackson ever made. I have stated previously that this was made from remaining stock before he retired in 1870 and given to Thomas Fairhurst.

On first impression the chair appears to be rather heavy in proportion, due to the legs and back members being almost the same diameter as for a full sized chair. There is some evidence to show that the chair was made very quickly. For example, the side view shows that the back is perfectly straight. Also the turned arms would have been much quicker to make than flat, carved arms. He did however take the time to set up the front legs on a double center in order to turn the pad feet. If I did not know that this was a Jackson chair it would be difficult to tell. The turned arms and most of all the lack of a top rail make this most uncharacteristic of his work. However its impeccable pedigree is convincing enough.

Was Jackson therefore a vernacular craftsman? Well, to begin with, he did follow established design styles which craftsmen both prior to and contemporary to him had evolved. The roots of the design of the Lancashire ladder back are obscure, but I feel quite sure that Jackson alone did not invent it. His own designs did evolve during his period as an active craftsman as I have suggested. Also he did make his own intuitive judgements, leading to refinements as he went along. He did use his material in the manner that had been proved to be most efficient and used techniques which had been handed down by craft tradition. He steam-bent the timber used in back slats and rockers, ensuring that there was no short grain in the rockers as would have been produced by sawing. He also turned most of his timber whilst sti1l green, to make use of its easier working properties and its ovalling during seasoning.

Jackson ran a one-craftsman business; he was not a cog in a machine, he was answerable only to himself. His power source for his lathe means that he employed at least two men, but these were probably only labourers. His business could not be described as an industrial concern.

Billinge chairs were certainly a product of skill. Jackson did design all his own work as far as I can ascertain. As for the point of standardisation there is no evidence to show that each chair was made individually. It is probable that he worked in batches, turning a number of legs, then a number of front rails and so on, so there must have been an element of standardisation. Any such standardisation as there was however was self-imposed; it was not done with the objective of matching up with the work of another craftsman.

I think it is almost certain that the type of chair that Jackson made was confined to the general region of Billinge and Wigan, as Bill Cotton suggests. Jackson was not a traveled man; as I have said he never went to local towns to sell his chairs, his customers came to him. It is possible therefore that he had only a limited knowledge of other Lancashire styles. This cannot be taken too literally however, because by the mid-nineteenth century communications had become quite efficient, more so in south Lancashire than almost anywhere in the country.

I think I can say that John Jackson was working in conditions that would fit my definition of vernacular. As such, he was one of the last remnants of a culture which had been torn apart by the effects of the industrial revolution. His ability to survive against the level of competition, which he must have been facing from industry, suggests that he was a remarkable man. All the struggling which I had to do to find information has been justified.

ST AIDAN’S CHURCH BILLINGE

About 1539 the people of Billinge, who till now had had to travel into the centre of Wigan to attend the Parish Church, decided that they should have their own place of worship within the village. A chapel of ease was built, paid for by the inhabitants, which, according to Rev Wickham, was probably similar in size and design to those which were built at Rivington in 1540 and Langho in 1557. The church at Rivington has been modified since then, Langho is virtually unchanged but is no longer in use for worship. It was almost certainly very poorly furnished, for when the King’s Commissioners arrived in 1552 the only thing, which they considered worth taking was the bell!

St Leonard’s Church, Old Langho

According to Rev Wickham’s booklet ‘Some Notes on Billinge’ the most likely site of this chapel was where the present Church of St Aidan stands. It is an impressive thought that the people of Billinge have worshipped God at this spot for more than 450 years. The sixteenth century was a time of great upheaval and confusion for the Church with the Church of Rome and the Church of England being ascendant in turn. When Queen Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558 Protestantism was finally established as the national religion but for many years after that there were problems in Billinge. The local gentry were mainly Roman Catholic and the chapel, which had by now become a Protestant institution was in poor condition and did not have an ordained minister.

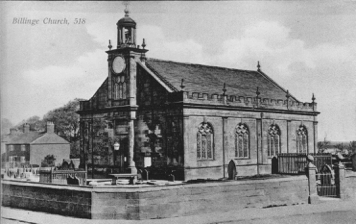

By 1718 a new chapel had been built which was one of the finest in the area at that time. Unfortunately the name of the architect is not known though St James’ Church in Over Darwin, designed by Henry Sephton and built about 1720, is very similar. It is known that a James Skaesbrike was a prime mover in the construction of the new building, a memorial to his generosity can be seen on the South wall of the nave, and that the Bankes family also made an equal contribution. It is unfortunate but we know little about Mr Scaesbrike except that he was a Liverpool merchant who had relatives at Winstanley. The new church was a rectangular building with a small apse at the East End.

St Aidan’s, the church built in 1718

This chapel had a capacity of 200 at a time when the population of Billinge was only about 900, an expected attendance of more than 20% of the residents, we would need several extra churches to accommodate so many today.

In 1823 and 1824 the capacity of the church was increased by the addition of first the north and then the south galleries.

Interior showing box pews and side galleries

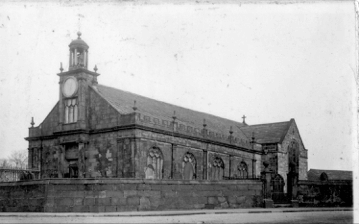

In 1907 a celebrated architect of the time, Mr T G Jackson RA, was employed to extend the church, the apse was moved eastwards and the choir and transepts were added. If one looks at the outside walls of the building the newer work is easily identified by the different stone used to supplement that already available. At this time also the galleries and the box pews were removed, the oak panelling of which the pews were made was installed all round the church and is still to be seen there today, if you look closely you will see the marks left by hinges and catches from the old pew doors. The brass lectern was given in memory of Canon St George and is a copy of that given to York Minster in 1686.

The village war memorial is located in St Aidans in the southeast corner of the nave. The names of all Billinge men killed in the two World Wars are recorded here. The church organ is a memorial to those killed in the Great War and in the graveyard are three graves of men who died as a result of the wars. The Remembrance Day service is held here each year and new wreaths are laid on the memorial.

In the centre of the nave hangs a brass candelabrum, probably dating from 1718 and similar to those at Up Holland. Prior to electrification the church was lit by means of this and a number of oil lamps which were situated where the present electric lights are.

St Aidan’s after 1908 restoration

Obviously, also at this time, there would have been none of the floodlighting we now have to illuminate the chancel. The church must have been very dark in those days.

There is a fine brass lectern, given in memory of Canon St George by members of his family in 1909. It is a copy of one given to York Minster in 1686, and replaces the earlier one, which was melted down by the Puritans.

INCUMBENTS OF BILLINGE CHURCH

The Rev D W Harris has given us a list of those who have ministered at St Aidans. This list is not complete and does not include assistant clergy.

1609 – 1625 Richard (‘Reader’) Bolton

1625 – 1626 Edward Tempest

1626 – 1627 Peter Travers

1628 – 1646 ?

1646 – 1662 John Wright (The Puritan Minister)

1665 – 1666 John Blakeburne

? Goulbourn

1685 – 1699 Humphry Tudor

1699 – 1704 Edward Sedgwick

1704 – 1707 John Horrobin

1708 – 1748 Humphry Walley

1749 – 1763 Edward Parr

1763 – 1776 Thomas Withnell (Dispute over patronage)

1776 – 1813 Richard Carr

1813 – 1833 Samuel Hall

1833 – 1853 John Bromilow

1853 – 1898 Howard St George

1899 – 1934 Francis B Anson Miller

1935 – 1949 Arthur White (Archdeacon of Warrington)

1950 – 1952 John D Jones

1953 – 1966 W Kenneth Strickland

1967 – 1981 Derek W Harris

1981 – 2000 Dennis Lyon

- Sam W Pratt

BILLINGE CROSS

Not a part of St Aidans but surely associated at some time was Billinge Cross, mentioned in a document of 1555. It is thought that this cross was located at a boundary of the Winstanley estate. Its location would have been at the junction of Main Street with either Newton Road or Beacon Road, both close to the church. Cockersand Abbey formally owned the land around Billinge and it was usual for boundaries of such properties to be marked with crosses. The cross was probably destroyed by Cromwell’s men though it could still be found one day by someone excavating for a new building or will it be found forming a lintel or stone step in one of the older stone buildings in the village. We will just have to wait and see.